I’ve more than once noticed some interesting links between mindfulness and performing classical music. It might seem a bit esoteric, so bear with me. This article is not just about music; it is about the parallels between executing a craft and different states of mind and productivity.

I am a classically trained pianist. During high school, while others practised sports, I practised scales; while others warmed up for their Saturday match, I was trying to keep my fingers warm while waiting to go on stage at an Eistedfodd (basically like an open exam, with what they called “adjudicators” who gave you scores). I did all the exams. I also play flute, but haven’t picked it up in years, and I sing in a choir. I still play piano a couple of times a week and am trying to do it more often because I love it – more than love it, it lets me access a unique space of both pure expression and deep personal agency.

Also, playing music does amazing things to your brain (both improving focus and protecting against ageing), your mood and your physical health, as does singing.

Music saved me. It was something I could call my own, something I was finally able to work and get better at after spending my whole childhood trying to avoid ball sports.

As a classical musician, you learn all about the discipline that goes with striving to perform a piece of music flawlessly. For me back at high school, the daily drill was to practise each of my piano pieces three times slowly, on top of all the scales and arpeggios. As a rough analogy of how the three-times-slowly routine worked, imagine stop-motion animation. It’s like you are rehearsing “frame by frame”, slowing a piece down to quarter-speed, moving and freeze-framing from one bar to the next in order to tweak and perfect each finger sequence, the rhythms, the changes in dynamics.

Then there’s performance, the actual goal of all the practice. And here’s where everything gets sort of flipped upside down. After all the work that has gone into learning a piece of music, when they finally perform, classical musicians are not so much making music as much as “rendering” it. In trying to execute a perfect rendition of what someone else wrote, they’re not playing it so much as pressing “play”.

Let me explain. Of course it’s “making music”. But in classical music at least, while there is some individual interpretation, you’re not improvising or trying something new; you’re trying to play something exactly as someone else intended it – all of the notes, with all of the performance directions in place. But to me the most interesting part of performance is the automation involved.

I’ve read that the brains of classical musicians, and also professional sportspeople, are amazingly quiet in the middle of a performance, because they are in essence executing a perfectly learned sequence of muscle movements. No thinking is necessary. Hence my describing of “rendering” a performance.

So, going back to the practice, what you’re doing is a kind of imprinting. As I said, there’s some interpretation involved, but the “making it your own” happens before you get to the stage. And it’s almost like “learned by heart” actually means “learned by body”.

In classical music, if you lose your place while performing something you ostensibly know by heart, you’re stuffed. It’s like all those hundreds of fine-motor sequences have been compressed into a single whole; you’ve learned one thing, one way, from beginning to end, and if you’re pulled out you have to start all over again.

I’ve been able to play pieces I learned in Grade 12 (18 years ago, *cringe*) without thinking. More specifically, I’ve only been able to play them without thinking. My muscles know the music, not my brain. And now that I’ve started dabbling with teaching myself jazz, and am having to revise and expand my music theory, I’ve “retaught” myself pieces that I could already play by slowing them down and working out the chords. It’s like a bizarre kind of reverse engineering.

And so I wonder, firstly: is it possible to perform something 100% accurately if, in spite of all the practice, you’re at risk of essentially falling asleep while going through the motions? And secondly, how much of life are we “performing” on autopilot, like a piece of classical music?

The perfect version in your own head – or getting dropped by the beat

Is it actually possible to play something 100% perfectly, full stop? I know I never did; I’m sure I never did – and right there you have the mentality of a classical musician, albeit an amateur. If you want to hire somebody who comes with built-in self-discipline, a sense of self-punishing conscientiousness, somebody who knows perfection is impossible but yet tries to go there anyway, someone who starts a project early and still finishes at the last possible minute (wait, that might just be me)… hire a person who plays a classical instrument. Looking back, classical music performance reminded me of watching Olympic gymnasts: they get off the mat and immediately burst into tears.

Usually in music, probably more so than in gymnastics (because, obviously, it’s easier to observe differences in movements made by those with gross motor control, rather than those who can just move their fingers super-fast), only the performer knows how many mistakes they made.

Do you know how many notes there are to get “right” in a piece of classical music? Especially if it’s a piano piece, which can have as many as ten notes piled on top of one another at any point. Every note has its own requirements for how loud it must be relative to the notes on either side, how long it must be held, whether it must be hit violently or gently or something in between, what mood you must be trying to magically evoke while hitting it – let alone the fact that you have to hit the right key to start with.

This brings me to a key element of the mechanics of music: time. It might sound patently obvious, but music would be impossible without time. If there were no space between one moment and the next, sound would have nowhere to go and there could only just be one big noise, or no noise at all.

More importantly, time is what connects the performer to the audience. If you miss a note, the audience doesn’t care, because they’re likely to be less trained than you on average, and probably won’t know all the notes in your piece (see above – classical pieces tend to have a lot of them). But if you miss a beat, the audience cares, because everyone has a built-in sense of time and rhythm (to a greater or lesser degree). And this is where the link between the music in your own head – your “perfect rendition” – has to be made with the music in the audience’s heads, which is happening live.

Messing up a performance is, in part, about losing track of where you are in time (“losing your place”), or of getting distracted and then – critically – getting worked up because you just made a mistake (which the audience didn’t notice, by the way) and then got preoccupied with that when, in the meantime, the piece is continuing to run without you (or at least it should – that’s what the audience really expects).

You look up and realise that the world has moved on.

Flow versus performing life on autopilot

How much of life is like that? Like we’re moving through, in our own zone, essentially unconscious?

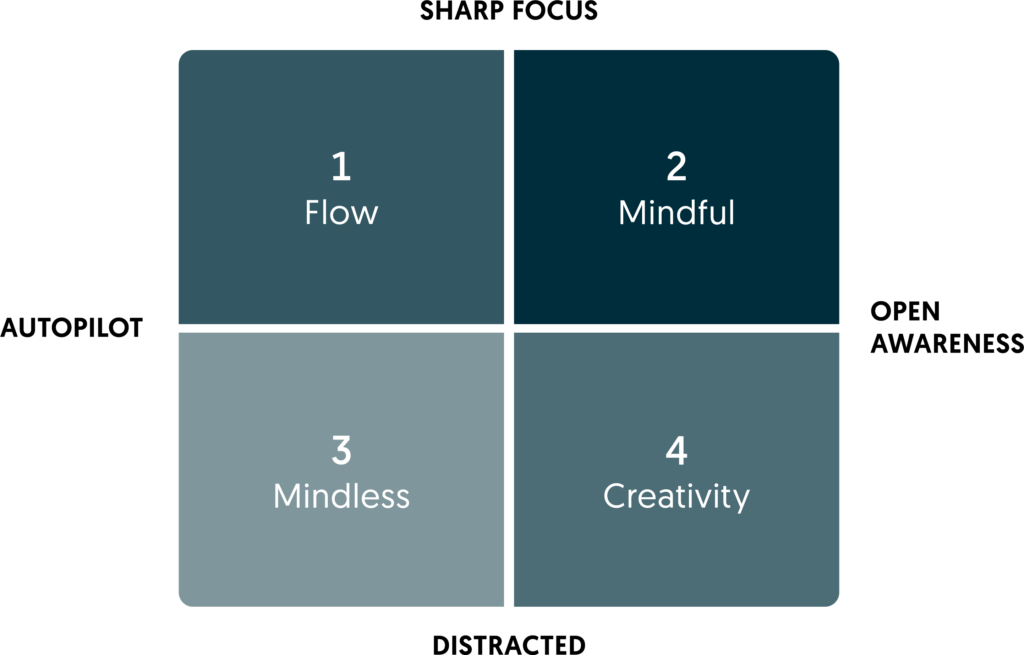

Relevant to this is a 2×2 matrix I once saw in a blog post from the organisation Potential Project, comparing four different mind states according to their degree of focus on the one axis (“sharp focus” versus “distracted”) and awareness on the other (“open awareness” versus “autopilot”). Here it is:

I noticed that it defined “flow” as being in a state of sharp focus but without open awareness. At first it seemed to me contradictory to be able to focus on autopilot, but then it began to make sense: You are in the zone, but nothing else exists.

If you know what flow feels like, I think you’ll agree. Flow means you are so engrossed that you “become” the work. You know what to do, so much so that you can almost check out, stand back and watch.

One thing I can say is that it can be quite blissful in the centre of that storm of muscle movements, imprinted into muscle memory, which is the quietest thing of all. That was music for me – going into another world. But it’s rather self-referential, rather like checking in but at the same time checking out.

On the other hand, mindfulness is supposed to be complete wakefulness, complete flexibility, complete readiness. It’s one-pointed but at the same time completely relaxed and open. Accordingly, the same 2×2 matrix defined mindfulness as “focus + openness”.

Is it possible to perform a concerto like that? I hypothesised that this would essentially mean staying 100% focused on every single note at all times, never spending a second dwelling on a single note you might have missed, and maybe not even thinking that far ahead. But surely that would be the same as flow, i.e. complete focus and autopilot? After all, if you’re there to execute something pre-written from top to bottom, what other information would you need to be open to taking in?

Being open suggests that you remain receptive to other stimuli around you, which in the case of music would include, most obviously, the audience. Now, classical musicians will know that when they perform, the audience all but vanishes. In fact, ironic though it may be, I’d put money on many of us wishing the audience wasn’t there in the first place. I swear I never play better than when there’s nobody around to watch me (key point: watch me, not listen to me). Perhaps, though, performing in a mindful, open state would involve at least sensing the audience’s state. You would need to remain “switched on” enough to be conscious of their response, because music is, after all, a form of communication – but without being totally distractible (by things like, for example, those beloved elderly concert goers who insist on fiddling with wrapped sweets mid-recital).

How often does your “audience” vanish at work, in life?

There is a lot of evidence that suggests that in order to get meaningful work done, we need to make our “audience” vanish for considerable periods of time. Creative output, deep work, thinking work – all these require silence and being undisturbed. Not only this, but they require spaced-out time too – research suggests we need gaps in between our focused sessions for all the dots to be connected, some of them at an unconscious level.

We can’t produce deep work if our attention is being drawn in all other directions at once. Likewise, we can’t listen to ourselves if we have to listen to others all the time – although of course, sometimes that’s our job.

Unfortunately, somebody gave management the idea that open-plan offices were the way to achieve higher productivity. So, how’s that working for you? (Or rather, with COVID-19 in mind, how did it work for you when we were still allowed or even required to go to shared workspaces?)

Introversion and extraversion aside, I know that managers sometimes have it hardest. When my husband was managing a team, he would describe how whenever he had that one gap in between meetings, he would get swarmed by his direct reports the moment they saw him walking from the boardroom to his desk. They needed help with making decisions, no doubt, and I wonder how many of those pressing questions and uncertainties they had were things they could resolve on their own if they just had the space to do so.

How much each of us needs to think “out loud” and with others, and how to do so effectively, is a topic for another day, but the point for now is that we need to be able to shut out the rest of the world from time to time. The research suggests that open plan offices are, in fact, a productivity killer. They were surely invented to improve productivity mainly from the perspective of cutting costs associated with office space.

Cultivating space where you are audience-free is important. I feel particularly for those with small children, who say they basically have to put personal space on hiatus. But I think an important thing is that if you do manage to safeguard your spaces of sanctuary, whether those are deep flow or mindful alone time or both (recommended), you can return to your “audience” with a better capacity for being mindfully present with them.

The problem? If we don’t have any of this, if we can’t visit all the quadrants, we fall back into mindlessness, where noise becomes our quiet, safe space.

The quiet noise of now: Closing thoughts during lockdown

During a Zoom workshop I was part of the other day, my colleague mentioned that the worst and best part of this whole situation is that we can’t avoid ourselves. I’ve spoken about noise being our quiet, safe space, and in this instance I mean the noise we generate on a daily basis, mostly outside but also inside, to drown out the real “noise” within us. In essence, it’s the distractions we attend to and also generate to avoid listening to what’s inside: our true feelings, fears, desires and needs.

The streets are quiet. There’s nowhere to go to, no offices or coffee shops or malls; you can even have your food supplies delivered. If we’re lucky we can hear birds. Or some crazy neighbour in possession of a guitar, an amp and a rooftop terrace.

So the inside noise gets louder. I’ve been struck these past few days by the loudness of online content in particular. It’s positive, enlightening, inspiring, heartening content for the most part; but for me it’s still loud. Thankfully I have the absurd luxury of access to green, outside space, so I can listen to birds as well as inner narrative, after I’ve had enough of all the WhatsApp videos. And, of course, meditate.

I also – Hallelujah! – have access to a piano.

May you find the space to be at home with yourself.