The attempted cognitive reframing of a chronically anxious person (and suspected hypochondriac)

I’ve been accused of being a bit of a hypochondriac; worse, a malingerer.

The latter came from a physiotherapist, whom I was seeing for stiff Achilles tendons or something, and who quickly became used to my “what if’s”. “What if it’s this? What if it’s that? I looked this up and I’ve heard that this can happen… do you think I should try this? What if it doesn’t feel better in a week, two weeks, ever??” (And, of course, “When can I go running again?”). I can only imagine that anyone in the medical profession silently wishes for a ban on Doctor Google.

To be clear, the “malingering” thing was decidedly tongue-in-cheek. I’m not talking about being accused of having imaginary pain (in my last post, “All in your head”, I delve into many of the complexities and assumptions around chronic pain and the like) – although admittedly my Achilles problem was very minor. I’m talking about fixating on pain, in a way that makes others wary that I’m somehow making it worse; and, specifically, arming myself to the teeth with every bit of information I can lay my hands on to try and understand it and guard against more of it.

In my case here, knowledge isn’t power as much as it is my default strategy in the face of any uncertainty, doubt or indecision. Knowledge may be power in theory, or in certain circumstances (maybe, I don’t know, for people who have an actual qualification in the subject as a baseline), but it doesn’t necessarily empower me, because it certainly doesn’t put my mind at ease.

For me, and I’m sure for many, gathering information is a coping mechanism. It’s a distraction. It’s a strategy to create the impression of being productive and in control. It’s a way to avoid discomfort. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always allay anxiety – in fact, quite the opposite is often true.

But after much research and reflection (my other obsession), I’ve started to consider whether perhaps I need to reframe the way I think about these compulsions, instead of trying to fight or fix or apologise for them. Instead of seeing them as the strategies of an incurable neurotic, maybe I need to tell myself a different story.

The story I have been telling myself is this: I couldn’t stand it if I wasn’t in control.

Also, beneath all the information gathering about health and even all the things I do to positively maintain my own health (which themselves may sometimes tend toward the obsessive or aggressive – for example, feeling compelled to exercise after eating pudding, or buying all the supplements and smashing raw garlic and lemon in my face the moment I get a sniffle) is the assumption that I couldn’t cope with being unhealthy or in pain.

Or even, I can’t stand being anxious. And within that: Being anxious is a bad thing.

One of the most empowering perspectives I’ve been given in recent years, which had never occurred to me because I assumed it was a sign of weakness, was that troubleshooting can be a strength. It can actually be valuable to have somebody in the team who’s spotting every single thing that might go wrong, every last flaw in the plan, every bleeding typo.

But what about how I make myself feel? Why does seeing all the mistakes in the world still make me so darn upset?

I’ve assumed anxiety will disarm me, ruin me, incapacitate me – and it often does. But maybe it does because that’s what I think it will do.

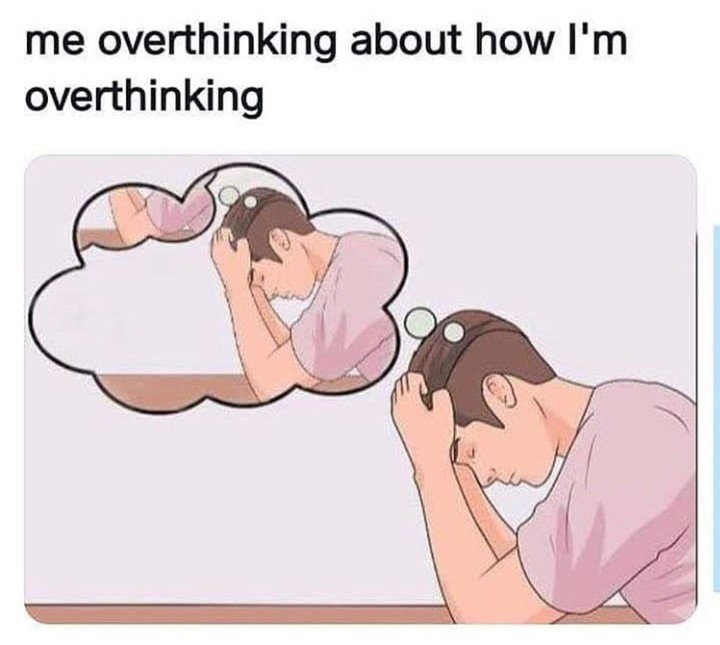

Being anxious about being anxious

Russ Harris, an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) trainer and author of The Happiness Trap, talks about something called The Struggle Switch. When we face a hardship and it upsets us, we either accept it for what it is and/or do something about it, or we “flip the switch”, as it were, and start to struggle with it. We get upset, indignant, annoyed or even guilty, not just about the situation but also about the fact that we’re feeling the way we do about whatever’s happening (or not happening). In short, we get anxious about being anxious. By fighting to get rid of it, we amplify it.

This, I think, is the story of my life.

Anxiety is a productive emotion – if we can see it that way. It prompts us to take action, to help ourselves and others, to seek or give support. It can be a productive and creative force. Whereas I’ve often just assumed anxiety is a sign that I’m a person who is unable to cope with life as it is.

There are personality factors and probably also cultural and gender socialisation dynamics at play here, among other things. For example, depending on who are are and how you were raised, you may have learned that avoiding, accommodating , acting or even becoming aggressive were acceptable or unacceptable responses to anxiety and fear. You may have learned to cope with fear by internalising it, or brushing it off, or pushing it back.

Where my own chronic fearfulness comes from is another story, but to work with it differently, maybe I need to see it differently, or call my response something else. So, how might I reframe my anxiety and worrying behaviour, whether it shows up as knowledge-hoarding or otherwise?

Reframing worry

Instead of seeing worry as a sign of weakness or defence, I can try see it as a sign of strength and proactiveness. How might this look?

- Rather than “I’m doing this because I’m worried/scared that…”, I could think: “I’m doing this in order to…”

- In this way, the Worrier becomes the Trouble Shooter or Devil’s Advocate; the Pessimist becomes the Pragmatist. Worrying becomes a tactic to prevent real crises, rather than a continuous spin cycle of imaginary problems and unlikely or unrealistic eventualities.

- In a team setting: instead of “stopping the process” and “throwing spanners in the works”, I am refining, reshaping and making it more robust.

- Instead of feeling insecure, I can see myself as the securer; instead of retreating in the face of uncertainty, I see myself as able to create certainty.

- Even better, anxiety can be a prompt for curiosity and creative resilience, instead of retreat or defeat. Uncertainty then becomes something I am able to accept (which is important for all of us, if you’ve seen the world lately).

In short, anxiety prepares me and helps me to help myself and others; it doesn’t have to disable me if I don’t let it.

(On that: a TED Talk I once saw showed that if we’re able to see stress in this way, as preparing us for action rather than threatening to melt us down in a frazzle, it actually changes our physiological response for the better, specifically by helping blood vessels to stay relaxed instead of constricting.)

In this way, something that “I can’t help doing” then becomes something that is part of my style, one of my resources and contributions – because, just as important, it’s not all of who I am.

Productive worry

This isn’t so much a conceptual reframing as a pragmatic one, to keep the act of worrying in check. For those of us who worry about everything, an idea I’ve come across several times is to worry on purpose and within boundaries. Instead of trying to avoid or resist your worrying, try scheduling worry sessions. That’s right: set aside time – limited time, perhaps half an hour – to get your worrying done, and then sit down in a quiet spot, with a notebook and pen, and do it. And then stop at the end and do something else.

Have I gotten this right? Not exactly. I do use paper and pen to brain-dump and, admittedly, try to analyse my worries. I do notice when it starts becoming counterproductive (I might sound like a “Let’s draw up a pro’s and con’s list” kind of person, but the funny thing about those lists is that they still don’t make decisions for you at the end). And I know then when to distract myself and treat those paper-and-pen notes as part of my (often circular) process. I’ve also tried to become kinder to myself about my second-guessing once I’ve told myself to stop worrying and my mind has other plans.

Welcome, worry

“Thanks, brain.” That’s what Russ Harris tells us to say to our incessant mental chatter. Because, let’s be honest, some of it is useful, and some of it is just too much. But this approach invites us to accept, rather than push back.

By acknowledging anxious thoughts instead of trying to repress them, but at the same time not taking them all too seriously, we are achieving a couple of things:

- We’re keeping them in the back seat – and keeping the struggle switch off. In a way, you’re treating your thoughts like a small, overactive kid, or maybe a slightly annoying, whiney teenager. You let them mess around and come up with stuff that may or may not be useful, but you stay in charge, without needing to fight with them.

- We’re able to own them, and then let them go. Your anxiety is part of you. Like the small kid or annoying teenager, you don’t disown it – you give it a safe space.

- We’re able to take care of ourselves. We can be compassionate with ourselves only once we’ve recognised what is going on inside us. Repressed anxiety gets carried around in our bodies as tension and pain – this is something we can begin to process once we’ve acknowledged it.

In his book, You Are Here, Thich Nhat Hahn speaks about being here for our hearts and, therefore, here for our emotions. “I am here for you, my anxiety/worry/fear/anger”. In this way, we become a safe “home”, though not a final dwelling. Emotions are energy in motion, which means they are temporary. One of my favourite quotes, or part of a quote which has become almost an affirmation to me, is “No feeling is final” (Rainer Maria Rilke). Once anxiety is recognised, it is freer to move and move on, to transform and, perhaps, to loosen its grip on us.