Previously, I described realness as being about being seen. In this next instalment, I shift focus onto the realness, or reality, of what we see — specifically through the lens of privilege.

How much of the world is real to you? How big is the “real estate” in your mind? To me, one major aspect of reality awareness is recognising different subjective realities. In other words, I am moving from knowing the self to knowing and understanding others.

Some months ago, I watched a video interview with mental health therapist and educator Dr Kamilah Majied, who wrote the book Joyfully Just and whose work focuses on anti-racism and inclusivity through contemplative practice. During the conversation, which was part of a broader series on collective trauma healing, the author made a compelling point about privilege. Dr Majied said that privilege doesn’t just protect and advantage those of us who have it, it also constricts our reality in some ways.

The first problem with white privilege is that we don’t realise that we have it in the first place (the more important problem being, of course, our willingness to confront it). Robin diAngelo, the author of White Fragility, at some point used the analogy of swimming upstream: white privilege is about all those things that make our lives flow effortlessly, to the extent that we aren’t even aware of the metaphorical river until we become conscious enough to see it and then work against it. To me, this is a perfect nod to David Foster Wallace’s “This is water” message – and the key point he makes in the college commencement speech it is taken from, which is that the goal of education should be to see what we’re swimming in (or, as Wallace put it, “the most obvious, important realities [which] are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about”).

Majied refers also to WEB Du Bois’s concept of double consciousness. The American sociologist and rights activist’s original idea was that the oppressed person, as a necessary outcome of being made aware of their being different and “less than” from the very start of life, comes to develop at least two levels of self-awareness: they know themselves, but they also constantly see themselves through the eyes of the oppressor. The impact of double consciousness on the oppressed person, as I understood it from Du Bois’s main thesis, was to internalise the gaze of the oppressor and take oneself as inherently inferior (“measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity”, as he writes in The Souls of Black Folk). Closer to home, anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness movement drew on the work of Du Bois and on the recognition of this internalised oppression.

But something else comes into play when this idea of having multiple consciousnesses is turned outward rather than inward, as it were. One implication of essentially taking on others’ views is that it enables a kind of cognitive or epistemological flexibility, which I think roughly equates to what structural racism educator Ayo Magwood describes as perspectives consciousness. To quote Magwood, perspectives consciousness (a term she attributes to the work of Robert Hanvey in 1976) “involves recognizing that our differing viewpoints are the product of our distinct cultures and identities (“positionality”), as well as of our different lived experiences.” She emphasises that “…we will only be able to understand contemporary issues when we seek to understand the perspectives of various stakeholders instead of universalizing our personal perspectives”. She also points out that positionality is something that comes naturally to people who have had to cross cultural lines in their lived experiences.

To return to double consciousness, putting oneself in the shoes of the oppressor is in part a survival strategy for the oppressed, as it essentially allows the latter to anticipate the former’s next moves – particularly important, for example, when they have a gun. (The example that comes to mind is the sobering reality of Black parents in the United States having to brief their kids on how to behave if pulled over by the police. The message is essentially: “What matters is how it looks to the cop, not what your intentions are or whether or not you’ve done anything wrong.”).

The oppressor, on the other hand, does not need to develop any notion of the interior world of the oppressed. They need not understand their feelings, thoughts or desires, or learn any more than some basic shortcuts about the other’s culture – to do so would make them equally human, and that’s not how oppression works.

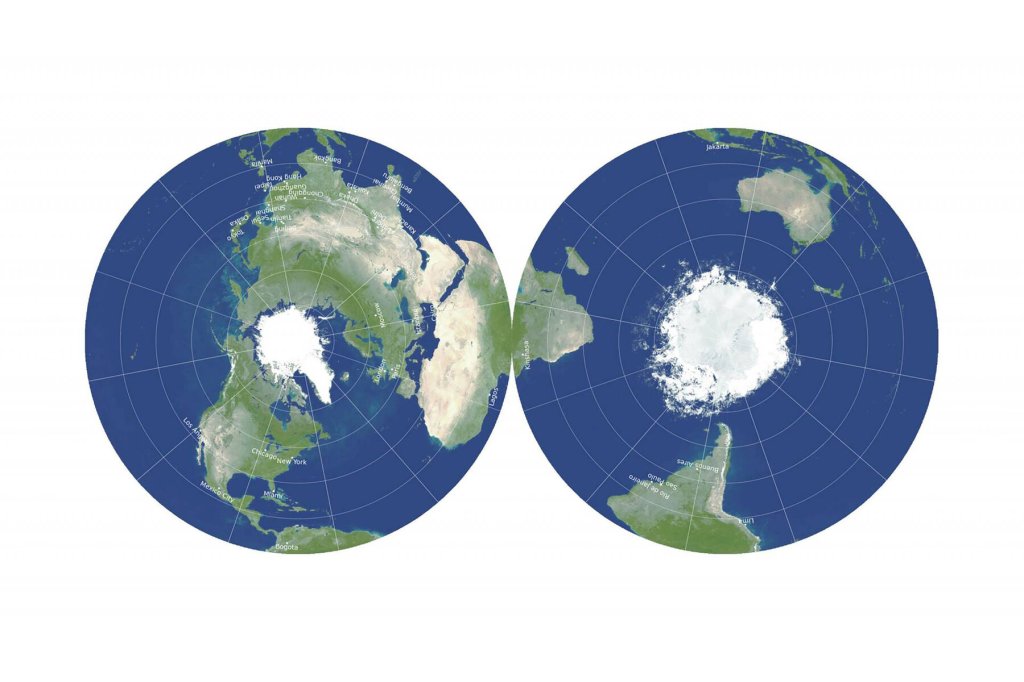

In short, people with power and privilege have not really needed to develop any “theory of mind” of people who are marginalised or different from them. It occurred to me that those in power (aka, for the most part in my view, white people), in effect see less than half the world. And they do not even know what they are not seeing.

The paradox, as it seems to me, is that those who are most seen, seem to see less. And this has implications for our broader systems of knowledge. If you think about it, what is “privileged” knowledge but partial knowledge? Knowledge only of that which those in power deem important, and have chosen to put in the spotlight or to define as “standard” – which could very well be a fraction of the knowledge of the world. And, of course, this goes with the assumption that those who don’t have privileged knowledge are not differently knowledgeable, but in fact ignorant.

An extreme rationalist view might discount the “realness” of subjective experience in any event; more common, I believe, is the discounting of other people’s subjective experience. In other words, my experience is real, and yours is not. What I do not see does not exist. Perhaps there is no better example of the insult of this than the words: “I don’t see colour”. The best summation I’ve heard recently of how this is actually interpreted is: “My whole life has been defined by the colour of my skin, so your not seeing that is your not seeing me.”

There are still others who would see authority’s view of the world as “real” and true, and one’s own subjective experience as not counting for very much. In a workshop I attended recently, a fellow participant spoke about the “Capital ‘T’ Truth” (ultimate truth, not privileged truth) and the “little ‘t’ truth”, which is one’s lived experience, and how both are equally valid. The workshop focused on using the Enneagram not just as a personality assessment, but as a source of insight into how our own and others’ “maps of the world” differ, so it was essentially backing up this point. But I think we have become systematically accustomed to discounting our own experience of reality.

I am aware that it is, to put it mildly, uncomfortable to suggest that one’s ability to see others’ viewpoints is prescribed by whether or not one’s ancestors were colonisers or enslavers, let alone the contentiousness of equating present privilege with historical oppression. One could argue that perspectives consciousness really comes down to the diversity or homogeneity of the society you live in (surely we are naturally more culturally aware in a country that styles itself as the “rainbow nation”?). It of course also varies on an individual level – and even if you have not had to assimilate to another, dominant culture, you might argue that you have voluntarily engaged with others who are different from you (as equals – key point). And most critically, as the work of Magwood and others clearly demonstrates, it is a skill that is flexible, that can be developed and should be taught.

I don’t wish to trivialise this by ignoring the fact that this “skill” of perspectives consciousness probably comes at a significant cost to those who have to learn it implicitly and by absolute necessity. I also cannot begin to claim that I understand these topics fully, let alone to have read WEB du Bois. I just found these concepts interesting as a way of illuminating 1) the work of perspectives and double consciousness, 2) how much more of this work those who do not have power or privilege have to do every living day, and 3) how perspectives consciousness should be seen as work that the rest of us need to be doing, if we wish to acknowledge the reality of others’ lived experiences.

The important thing that I personally took away from Majied’s and Magwood’s observations was a deeper understanding of white privilege and fragility: specifically, the idea that privilege can make us not only highly reactive and defensive, but also somewhat metacognitively impaired. The systems of power and privilege are a cost to humanity overall, but they also, in some ways, rob us of mental agility, vision and, frankly, imagination.

To simplify greatly, one takeaway could be, at the very least, to reflect on the extent to which we – unconsciously, but incorrectly – assume that the ways in which we see the world are the ways in which everyone else 1) does see the world, and 2) should see the world.