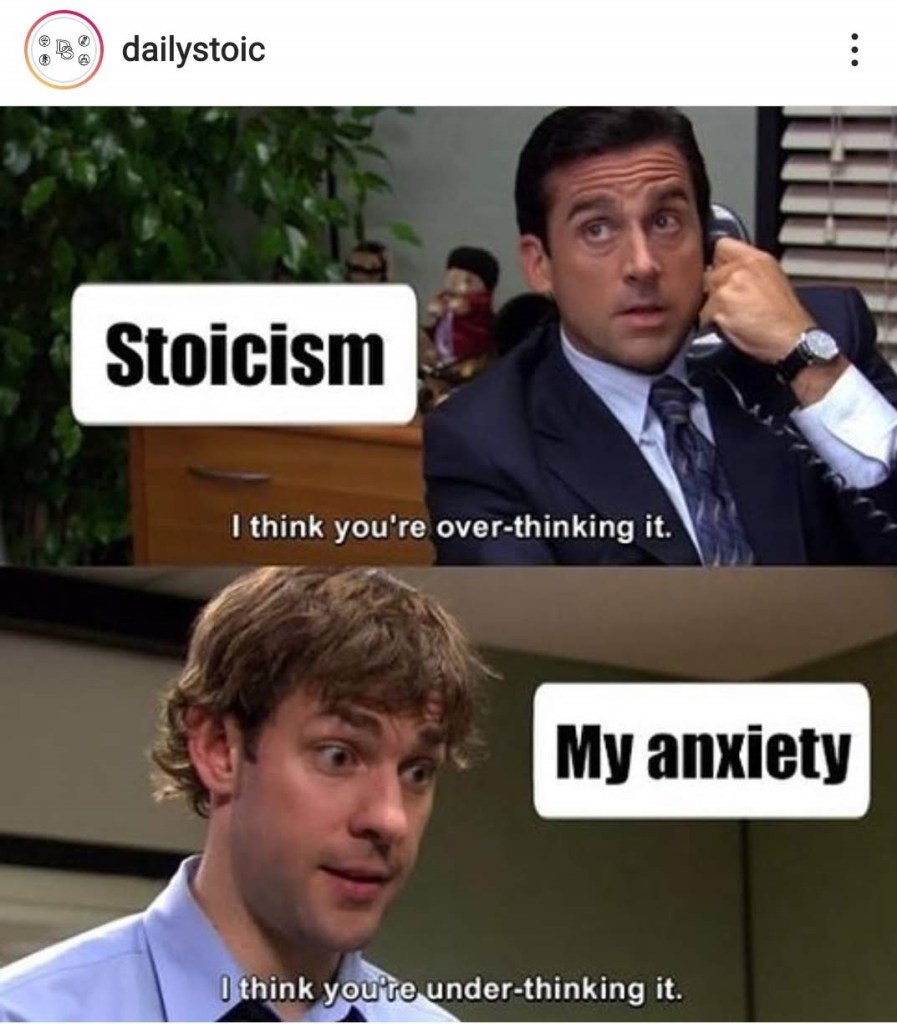

During a recent masterclass I attended on critical thinking, as part of a virtual internship for third-year quantitative students, one of the interns asked this question in the chat: “What is the difference between thinking critically and overthinking?” As someone who identifies personally as an overthinker, I thought it would be interesting to explore how we think about these two ways of thinking. What do we really mean by them, and how do they impact us as we navigate a world that is increasingly driven by (mis)information, data, and knowledge work?

In this particular series of masterclasses, critical thinking was framed broadly, alongside creativity and other thinking strategies, as a way of effectively approaching and solving problems. When the question about overthinking came up, one of the responses from the facilitators was essentially that overthinking can get you stuck in the problem-solving process, preventing you from arriving at a solution and moving forward. Thinking is one thing; reaching a conclusion and/or making a decision is another, and when it comes to applying critical thinking in the real world, the “litmus test” seems to be that it enables you to make a judgment and then act on it.

One question raised by the above is whether overthinking is simply critical thinking done to death or derailed. Put differently, can critical thinking turn into overthinking if you do it too much? Of course, there are various thinking strategies and styles that can lead one down the garden path, as it were. Again, the key assumption is that overthinking is not useful; it is, by definition, thinking excessively, or thinking that adds no extra value. I’d like to raise a few points around this, before getting into the detail:

Firstly, critical thinking might incorrectly be labelled “thinking too much” because the world is impatient and critical thinking is, frankly, effortful and time-consuming. As one of the interns commented later in the chat: “The real world moves too fast for critical thinking”. Sad reality though this may be, it’s a critical insight in itself. It makes us remember that if we don’t do critical thinking deliberately, it doesn’t come naturally – to any of us. With this in mind, we need to be clear on our definition of critical thinking because I believe it is, for the most part, qualitatively different from the kind of thinking that leads you into self-defeating spirals.

Second, I would like to add my own insights on overthinking, specifically relating to 1) how we present our thinking to the world, and 2) how it relates to anxiety and how we self-regulate while thinking. I think this is particularly relevant not only for people who are preparing to think and solve problems for a living, but for anyone who engages with concepts and abstractions on a daily basis – and, as thinking animals, that’s all of us.

What is critical thinking?

“Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterised by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artefacts and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion”. This is the definition used by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU), but it has also been adopted locally in tertiary education, by at least one university working to define critical graduate attributes for workplace success.

Here is another definition: “Critical thinking is a metacognitive process that, through purposeful, reflective judgement, increases the chances of producing a logical conclusion to an argument or solution to a problem.” – Dywer, 2004, cited here.

So, critical thinking involves exploration; it is a habit or a process, rather than just a skill; it belongs in the category of metacognition; and it is about more than just problem solving. Let’s parse a few of these elements further.

Metacognition, analysis, and stepping backwards to move forwards

In one of my previous jobs, I had a boss who liked to say: “Let’s all just take a step back”. I found myself often irritated by this catchphrase (as well as its associate, “Let’s look at the big picture”), not only because it is a corporate cliché but because it often felt like a call to halt progress or, even worse for me, to shut down the thinking process. (I joked to my friend that all we ever do here is walk around in reverse). But here’s the somewhat paradoxical thing: in order to move forward, you do have to zoom both in and out. Or, to add one more leadership buzz term, you need to “get on the balcony”.

How does this relate to the topic at hand? We just defined critical thinking as metacognition, which means the awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes, or otherwise commonly defined as “thinking about thinking”. The prefix “meta”, according to Wikipedia, means transcending or “on top of”. So critical thinking, if “meta”, is a little like “thinking from above”.

Let’s come back to critical thinking in the context of problem solving. One of the processes most readily associated with problem solving is analysis. And unsurprisingly, one of the terms associated with overthinking is “analysis paralysis”. So perhaps it is helpful to start with recognising that critical thinking is not the same as analysis. Analysis is about taking things apart; while critical thinking might involve this step, it is more than this.

Analysis, to me, is about how we treat the parts; critical thinking is about how we treat the whole as well as the parts. While analysis seems to generate more and more (more factors, more variables, more things to consider), critical thinking does this but then comes up with a plan to get to less. Maybe another (very loose) way of looking at it is that analysis generates things but critical thinking generates questions. It doesn’t just unpack items; it examines the box they came in.

The human edge?

While I am not an expert on AI and machine learning, these meta thinking processes – everything that falls roughly under the umbrella term “stepping back” – strike me as something that gives humans the edge over robots. In at least one of the other internship masterclasses, while discussing the process of preparing data for model building, the presenter highlighted the need to pause, scan through your data, and ask simply “Does this make sense?” Again, this is a “backwards step”, one without a detailed how-to guide – it’s basically looking for anything that stands out as odd. Recognising patterns and quickly spotting anomalies seem to be uniquely human aptitudes; they can even seem like intuitions, as when errors appear to just “jump out” at you from a screen of data or text. These “sixth sense” competencies are not infallible – our intuitions can be simply wrong – and they are often the product of years of experience. But in general, stepping back seems to be something that humans do more readily than robots.

Another thing that machines don’t do, which I think helps remind us what critical thinking is, is to turn around and ask: “Why are we doing this in the first place? Who wants to know? What’s their interest in the outcome? What’s really happening here?” The more I think about it, the more I’m noticing why we like robots – because even if they come up with weird results, they don’t talk back. For now.

Thinking and acting (in the half-dark)

Critical thinking, then, allows you to step back and see not only the problem as a whole, but also its full context. In other words, at its broadest it should allow you to understand the problem at hand but also recognise what the situation needs. With that in mind, let’s return to our original “litmus test” of critical thinking: that, unlike overthinking, it enables you to make a judgment and take action.

Here’s the thing: the action that you decide to take might be to collect more information. It might be to take more time to consider the issue. In other words, the outcome of critical thinking might be to do more thinking – but, crucially, this is an active decision.

Another perspective, which is very important in the reality of working with uncertainty and solving problems that nobody has ever seen before, is that sometimes you need to think about something enough to establish what you don’t know – and then move forward anyway. The key here is that you get more information by acting and observing what happens.

You might say, therefore, that critical thinking means being able to recognise what we’re achieving with our thinking processes – being able to think on purpose, or deliberate deliberately, so to speak. Overthinking, on the other hand, can be both perpetual and unconscious. One of my own personal reflections has been that overthinking can even be not thinking; a form of mental spinning that actually qualifies as thinking avoidance.

This brings me to the next section, which is to examine overthinking a little more. Is it merely analysis paralysis? What qualifies as “thinking too much”? And how does it impact us personally? Even if we work on the assumption that overthinking is unhelpful, it is helpful to understand it better.

Overthinking versus oversharing

Reflecting on my own working experience, when I have been told “You’re overthinking it” in the past, I suspect my mistake was not thinking so much as speaking too much.

Earlier I said that critical thinking gets you to less, not more. So here is something I have learned:

Just because you’ve thought about everything does not mean you have to tell your boss/audience/customers/stakeholders everything you’ve thought about.

Equally importantly:

Just because they don’t use all your ideas, or even if you don’t use any of your own ideas, does not mean your thinking was a waste. Generating ideas and options is only one part of the work of thinking; the more important and much harder part is judgment: deciding what to leave out based on what is necessary for now. Remember: critical thinking includes deciphering what the situation needs.

Mark Twain is quoted as saying: “I didn’t have time to write you a short letter, so I wrote you a long one.” The mark of good editing – and communication, and leadership – is simplicity. It can take years to master the art of finding what is most essential.

The above are lessons that have been extremely hard for me personally. As an anxious overthinker, I have only recently considered that I overshare my thinking in part because I equate transparency with certainty (which is not correct, but that is another story). In short, I might think out loud too much because certainty is important to me. Therefore, I assume that other people want the same level of detail and transparency as I do.

Which brings in another important metacognitive skill: perspective taking. Recognising what the situation needs includes recognising what your stakeholders need: putting yourself in their shoes and considering what is most important to them. Their anxieties might be completely different to yours. On the one hand, you may then need to set aside some of your own issues, not to disregard them but to address them in alternative ways; on the other hand, refocusing attention on their needs and on objective outcomes can give you a more structured guideline for what to prioritise, what to leave out, and when to stop thinking.

When thinking gets (self-)critical: Anxiety, metacognition and self-regulating

One of the reasons critical thinking is so hard is that it involves self-examination. It is far easier to act than to reflect, let alone entertain questions of whether or not the way we see the world might be flawed. It is a slow and deliberate process, in a world that constantly pressures us to have an opinion, pick a side, and buy a product as quickly as possible. Just giving oneself the space to be able to think critically seems like an uphill battle.

But here’s the thing: while critical thinking itself may be hard work, I would hesitate to call it stressful. Rather, in my experience, a key component of overthinking is the anxiety it produces. This is subjective, but it matters. And what makes overthinking anxiety-provoking is not just that it’s exhausting, but that it consists of mental processes beyond simply working on the problem at hand. Many of these processes fall under a category that might be called “self-talk”.

Here, then, is how overthinking can be “critical”: when your thinking is accompanied by an internal monologue that is more of a hindrance than a help. It may be the voice inside your head that is constantly judging you for how you’re thinking, or reprimanding you for thinking too much or too clumsily, or stressing you out with: “Are you sure you’ve thought about EVERYTHING? What if you’ve forgotten something? Have you considered what absolutely everyone might think?” Even worse, and probably more subtly, it could be quietly telling you that you will ultimately fail at this and all other tasks no matter how hard you try.

Now, please don’t get me wrong – I’m not saying that overthinking equals negative self-talk. I especially do not wish to pathologise overthinking, despite what I have just said about how it leads to anxiety – because after all, who decides how much thinking is “too much”? There are plenty of mental processes and divergent thinking styles that mean some people take longer to think about things than others, and /or arrive at decisions via very different routes. Importantly, too, I don’t wish to pathologise self-talk; rather, I want to emphasise how metacognition offers us a way of using self-talk as a constructive tool – one that might prevent us from being overwhelmed by anxiety and slipping into a flat spin.

Metacognition means thinking about thinking, but it can also mean reflecting on and monitoring how you are managing your own thinking and learning process. In the masterclass, the facilitators in fact used the term “meta voices” to refer to the mental processes of essentially monitoring yourself thinking through a task. In this respect, the self-talk is positive. It includes not just “signposting” yourself through the stages of the thinking process (e.g. “Right, now I think I have a good enough understanding of the problem, let’s move onto possible causes…”) but also keeping an eye on how you’re managing your cognitive load (e.g. “OK, I can see I’m going around in circles, I think I need a break and some fresh air now…”). It could also include being aware of the emotional energy that comes with having to revise your own mental models, receive critical feedback, and occasionally feel shut down by others’ seeming inability to acknowledge your perspectives (“Oh, I can see this is really making me feel defensive. What’s going on here? Why am I so offended by that?”),

What of critical thinking and self-critique? While critical thinking does require you to take a brave and honest look at yourself in order to interrogate your assumptions and blind spots, I do not believe it is the same as being self-critical. I think its value lies in its neutrality – its ability, once again, to step back and notice what’s really going on. Which may mean recognising that you have fallen into the same overthinking trap for the thousandth time; but then also recognising the futility of beating yourself up, and perhaps acknowledging that you were overthinking because you were feeling unclear about what was expected of you. Or because you needed a snack or had drunk too much coffee.

Granted, it is extremely hard to be completely objective and to spot the ways in which we fool ourselves, but metacognition can help us to recognise the patterns and triggers, and then take preventive action by setting ourselves up to think at our best. A final litmus test, then, of overthinking might be simply that it is unregulated – that is, un-self-regulated.

Admittedly, critical thinking and self-regulation are not the same thing, but with the broader idea of metacognition, I believe they work hand in hand. Maybe I’m taking liberties here, but in closing I would contend that critical thinking is not incompatible with being kinder to yourself – and more tolerant of others.

An adapted version of this article was originally posted on LinkedIn.