I once heard that the source of all anxiety is fear of the future, and the source of all depression is dwelling in the past. As a rough shortcut to understanding these two very common mental afflictions, this has appealing simplicity. But as one who has experienced both depression and anxiety, I have had a few reflections on the relationship between suffering and our orientation towards time, as well as our relationship with reality as a whole.

Now, I wouldn’t disagree that suffering, at least of the mental kind, is linked to the inability to be present. This very idea is at the heart of the mindfulness movement, whose essential principles might be encapsulated in the tagline “Be here now”. Nonetheless, it occurred to me that saying depression is all about the past and anxiety is all about the future can seem practically unhelpful, most obviously because both forms of suffering are experienced in the here and now. But also, it all seemed a little at odds with my own experience.

I have suffered periodically from bouts of depression, without being conscious at the time that I was dwelling on any particular past event, just feeling the overwhelming burden of present feelings – which, granted, were familiar, and which were probably the product of brain routings that had their roots in my own personal history, or even further back.

Also, I struggle with anxiety, but my experience is often that it is all about “managing the present”, rather than attempting to think about a future which, it often seems, I can’t even see into. Anxiety doesn’t feel like fear of the future to me; it feels like fear of the present moment – which may, admittedly, be a projection of a future which I made up in the past (how’s that for temporal whiplash?).

It struck me as ironic that, particularly given that I call myself a mindfulness practitioner, I can experience the present moment as a place of both great peace and happiness, and great suffering (the Zen masters are, no doubt, way ahead of me on this paradox). But what I found all the more interesting was that, given all this, I had never thought of myself as someone with an overall “present orientation”. I suspect this may be because I identify as a head type, and the head seems to operate on another planet entirely, let alone the same space-time continuum that the physical world generally agrees on.

How does our experience of mental suffering relate to our experience of time? For the purposes of this post, I am interested specifically in anxiety. When we are anxious, where in time do we tend to be placing our focus? Or rather, where do we believe we are placing our focus, and are we sometimes fooling ourselves?

Is it possible that what feels to me like a preoccupation with the present is actually a form of fearing the future in disguise?

Anxiety, imagination, and time travel

First up, what is anxiety really all about? How does it differ from stress?

Stress is commonly described in terms of the “fight or flight” response, which is shorthand for all of the familiar physiological mechanisms that kick in to prepare your body for action (heart pounds, pupils dilate, blood flow gets directed to the muscles, etc). The stress response is activated by external triggers that we perceive as threatening, but also kicks in when we need to perform under pressure, or whenever we perceive that we don’t have sufficient resources to deal with our current situation.

While stress is typically understood as a response to specific external stressors, anxiety is usually described as a more chronic state of apprehension, or even dread, which can persist even when external causes are removed. Anxiety, bluntly put, is internally generated stress (by which I broadly mean, for the purposes of this article, “mentally generated”. I am aware there are complexities around how we understand suffering that is generated by the mind versus the nervous system, and indeed how we can even begin to distinguish the interplay of all internal and external factors. For the purposes of this post, I am speaking mainly about mental habits that contribute to anxiety, and which are largely within our conscious control.)

The problem with internally generated stress is, of course, that it feels the same as stress triggered from the outside. Also, it works “out of sync”. Our blood pressure can shoot up as much in the presence of a physical threat as when we think about that same threat, or recall a past experience that caused us distress (research here highlights essentially how worry activates the body, not just the mind).

Anxiety seems specifically to be like chronic anticipatory stress — like believing there is constantly some sort of threat present or around the corner. Hence, “fear of the future” makes sense. Where it gets interesting is when we begin to examine what sorts of future “threats” we are preparing for, and how this translates into present behaviour.

Humans have the most remarkable imaginations, as well as the remarkable ability to mentally time travel. We can be anxious about a realistic future threat, or about the prospect of a stressful past event repeating itself. We are often also afraid of future threats that are entirely imagined: triggers that may never be pulled, as it were. A quote commonly (mis)attributed to Mark Twain goes along the lines of “Some of the worst things in my life never happened to me.” And in the words of the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca, we suffer more in imagination than reality.

If this is the case, maybe anxiety is better described not as fear of the future, but fear of an anticipated future. Consider the example of being anxious about having to go to a networking function. The stressful event itself has not yet arrived; nevertheless, you experience stress now. The trigger has changed from being in social situations to the thought of being in a future social situation.

And this leads us to recognise that, crucially, we can get stressed out or anxious by the prospect of becoming stressed out and anxious. Think about it: being stressed out is, frankly, unpleasant. When something happens that puts you in a bad mood, do you not also get peeved by the fact that you’ve been put in a bad mood? If we can get peeved about being peeved, can we not also get stressed about being stressed? The source of anxiety, or at least part of it, might then be the anticipation of getting anxious – or the feeling of not being able to cope with whatever might cause us stress.

With this in mind, I propose yet another modified definition of anxiety: namely, the fear of future feelings. This brought to mind another thing the Stoics have long warned us about, which is “suffering in advance”. It seems to me that one way in which we adapt to the fear of future feelings may be, ironically, to get them over with right now.

Suffering in advance: The cost of preparedness

At this point, let me return to how I described my experience of anxiety as “managing the present”, and attempt to explain what I mean exactly.

In my case, what comes to mind are activities that might be summed up as proactive coping. Simply put, I am a person who is sensitive to stress, but also pretty good at managing it. I manage my energy proactively (planning meals, exercise and meditation) and am good at monitoring (I notice when I need a break) and recovering (after a stressful day, I go for a run or do something else to blow off steam). When I have a sniffle, I tackle it guns blazing with vitamins and teas and naps. I would describe my approach to self-care as defensive (possibly even aggressive). I cope before, during and after stressful events that may or may not happen.

But a critical theme of the above, which relates back to my idea of “fear of future feelings”, is not so much their proactiveness but their defensiveness. Admittedly, many of the things I do which I associate with managing my anxiety could be seen as a form of pre-empting future feelings. Or, more specifically, defending against the possibility of future feelings that are likely to be uncomfortable.

I eat now because I am pre-empting hangriness later. I rush to get to bed because I am pre-empting feeling tired and grouchy in the morning. I make plans now because I am pre-empting feeling indecisive later. I clean the house now because I am pre-empting feeling annoyed by the mess later. I start working on something now because I am pre-empting feeling disorganised, or falling behind, or getting caught off guard.

All of which is very depressing. One might, alternatively, step back and reframe all of these behaviours simply as effective forward planning. Surely the pay-off is preparedness – if not genuine, then at least a sense of it? The question then becomes: at what cost? From the outside I might appear to be “high functioning”; what about on the inside?

The acid-test question, then, may be: Do these activities actually make me feel less stressed, or do they simply make me feel in control by effectively bringing the stress forward in my calendar? I wouldn’t go so far as to say that doing these “anxiety preventing” activities is stressful in itself (it isn’t, and it does usually pay off in some way), but they are effortful.

Part of me wonders whether coping behaviours make us feel more on top of things right now, or whether they make us feel like right now is on top of us.

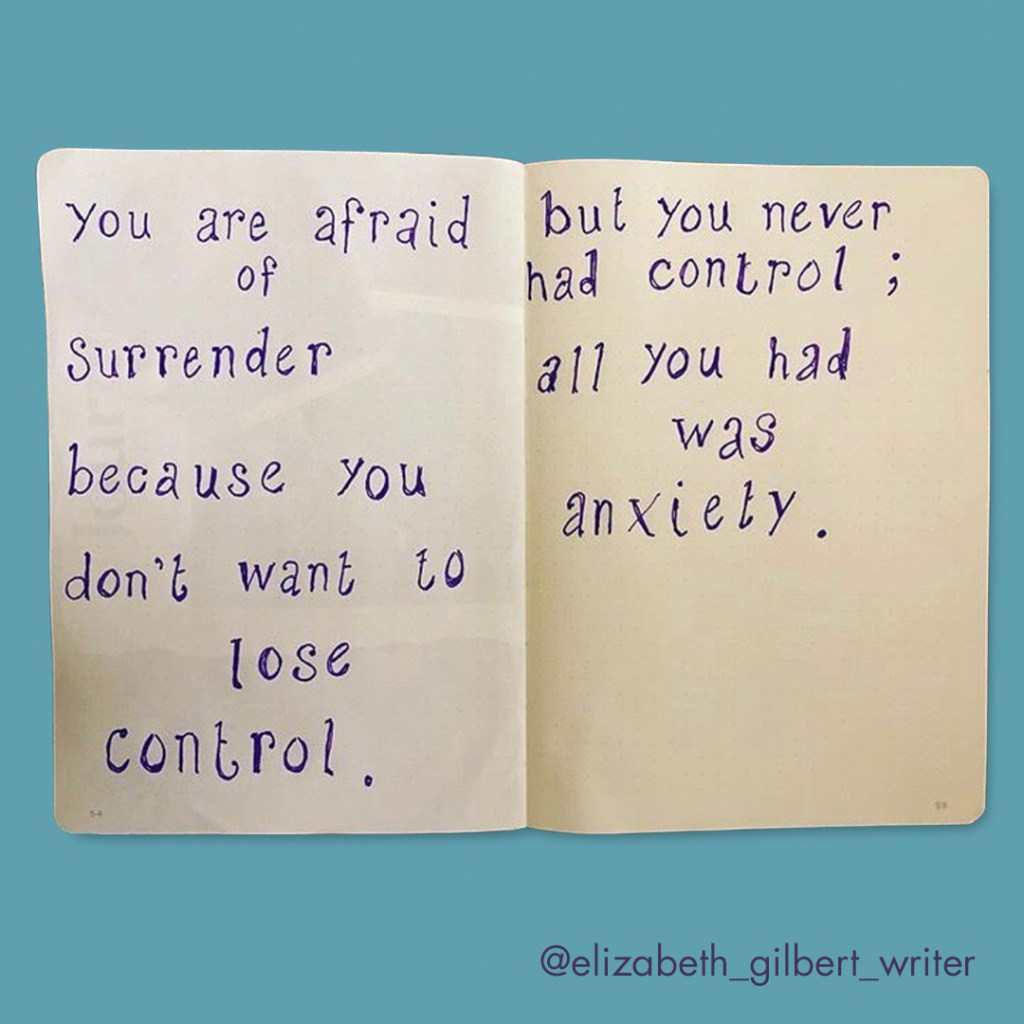

Image shared by Brene Brown on Twitter

Temporal Trickery

After all this, I came to the realisation that if “managing the present” really means “managing future anxiety”, maybe my game is up. That is, maybe one of anxiety’s main tricks, which I have clearly fallen for, is to keep us believing that we are focusing on the present, yet what we are actually doing is fixating on present minutiae in order to avoid thinking about the future in a deliberate and purposeful way.

Put differently, preoccupation with the present might just be obsession with the future in disguise. Whether we are thinking about it defensively, or refusing to look at it, we’re still orienting ourselves towards it.

Maybe a similar phenomenon is the tyranny of the urgent: we think we’re focusing on what’s most important, but it’s actually just what is most immediate – and smaller, and less scary. Related to this, I recently stumbled upon a new and rather more helpful perspective on why we procrastinate, which is that we do it to avoid not the work itself, but to avoid uncomfortable feelings of uncertainty or self-doubt.

After all, surely all anxious behaviour is, at some level, an attempt at engineering certainty?

Fear of change or plus ça change?

Given all this talk of fear of the future, one might naturally assume that what we are really afraid of is uncertainty, and in turn that this equates to the fear of constant and unpredictable change.

But then I sat back again and asked: why does anxiety feel like “fear of the present moment”? Is the present moment scary simply because anxiety feels so awful? Or is it scary because I am afraid it will never get better?

Is fear of the present moment, then, actually a fear that the present moment will continue forever? And fear of the future, by extension, a fear that the future will be no different?

In other words, we might think we are afraid of change, when in fact we are afraid of immobility. Or, probably more precisely, our own immobility – our own powerlessness.

This brings me to my final point, and one potential antidote.

Future casting: Try looking from further away

As we’ve seen, the ability to time travel can be a curse. But it can also be, if not quite a blessing, then a useful hack. We just need to take it to the next level – literally, by projecting ourselves even further into the future.

Psychological distancing, a concept developed by social psychologist Ethan Kross (among others), is just one of a set of tools broadly known as framing. Framing is essentially about changing your mental relationship with things that tend to cause you stress; psychological distancing does this in a prospective way. Dr Laurie Santos, Yale professor at the Happiness Lab, describes it as thinking about an upcoming event as your future self would think about that event.

Let’s say you have a stress-inducing interview coming up. Instead of worrying about every possible curve-ball question that might come up, you would ask yourself: “How would future Fran like to think about this interview?” Or “What would I want my future self to be able to say about it afterwards?” The answers might be “That I showed them who I really was”; “That I had a really interesting and engaging conversation with them”, etc.

The most important point is we can use this technique to shape our future experience. Yes, it can prepare you for some of the detail – for example, you might say to yourself, “Future me wants to be able to say X – and this means I want to be sure to focus on Y…” – but my take on it is that it’s not about the “fine print”. Rather, by zooming out in time, we are also zooming out on another key driver of anxiety: detail.

Ultimately, what you are asking yourself is how you want your future self to feel, rather than using it to prepare ourselves for every possible eventuality (indeed, in this paper co-written by Kross, it seems that the more vividly people imagine future stressful scenarios, the more distressed they become). We’re future-casting our state, thereby enabling ourselves to act into the moment rather than worry interminably in anticipation of it. Or, at the very least, we’re giving some focus to our preparations by reminding ourselves of what we ultimately want.

Distance, in other words, gives confidence.

I will readily admit that I am the kind of person who is still learning to be less prepared and more trusting of my ability to respond in the moment. I still have meetings with people before they even happen. But do I think about how I want to feel after them (rather than catastrophising about how I’ll feel if they don’t go well)? And another thing: If I were to look back, I might realise that I’ve all but forgotten about the meetings that did go badly in the past. What if I applied that insight to the next meeting in my diary?

Here, then, is a critical important point about how this futuristic self-distancing trick works, which links up very nicely both to the fear of future feelings and the fear of those feelings overwhelming you and never going away:

Thinking about how you’ll feel about something in the middle- to distant future reminds you that your stress, and ultimately all of your thoughts and feelings, are impermanent.

In a way, this is like the ultimate hack for fear of the future. The very thing we’re scared about is what can give us the greatest sense of relief – the fact that nothing stays the same.